1 April 2012 is a happy day for the Carey family. Our son David is marrying Constance Patterson today. We've enjoyed getting better acquainted with Constance and her family over the past three years. Somewhere along the way, we learned that our new daughter-in-law is descended from one of the greats of traditional jazz and swing – trombonist Brad Gowans.

Constance, as an adopted child, was unaware of her relationship to Brad until she was about 30 years old and met her birth mother.

As a jazz fan, I had heard of Brad long, long ago. He played the valve trombone on many classic records during the thirties and invented a hybrid instrument called the valide trombone, which included a slide, as well as valves. He also played cornet and clarinet from time to time.

Brad Gowans' biographies are available at:

From these sources, and from the U. S. census and other public records, we can learn a few basic facts about Brad. He was born Arthur Bradford Gowans, 3 Dec 1903, in Billerica, Massachusetts, and died 8 Sep 1954 in Los Angeles. In 1910, he was living a few miles away from his birthplace, on Crescent Avenue, in Bedford, with his parents Arthur and Ellen, and younger brother Horace. Brad's father registered for the draft during World War I, 2 Sep 1918 in Arlington, MA. See his draft registration card, which we found at ancestry.com, and which was transcribed as follows on a forum at genealogy.com:

Arthur Gowans age 45 born May 6, 1873 medium height and build, blue eyes, gray hair address - #38 Newcomb St., Arlington, Mass. Occupation - Supt. of Storage Battery Employer - Electric Storage Battery Co., #72 Beacon St., Boston, Mass. Mrs. Ellen Frances Gowans, wife, #38 Newcomb St., Arlington

We couldn't find any trace of this family in 1920, but in 1930, Brad was gone (on the road with a band?) and Horace was still living with both parents at 40 Newcomb St., about 10 miles farther south, in Arlington.

Brad worked in several little-known bands in his early days before joining famed violinist Joe Venuti on cornet in 1926. Gigs followed with Mal Hallett's big band and with Jimmy Durante, who was a pianist and bandleader in the Twenties before becoming famous as an actor and comedian. Although he was in and out of the music business due to the Great Depression, Brad played and recorded with many of the the leading figures of early jazz. He made very few records under his own leadership, though, so he seems to have been forgotten by all but the most hardcore of jazz enthusiasts.

Brad married a woman named Juliet Malonis, the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants Michael and Mary Malonis, and they had one child, Shirley Gowans, who was born 8 May 1928. Shirley is Constance's mother. Brad and Juliet divorced before the 1930 census, when Juliet and Shirley were enumerated in Arlington, MA, living with Michael and Mary at 11 Orvis Road, about two blocks away from Brad's parents and brother. This family of four was still living in the same house in 1940.

On 14 Jun 1932, in Salem, New Hampshire, a marriage was recorded for Bradford A. Gowans, age 28, the son of Arthur Gowans and Ellen O'Keefe, to 23-year-old Louise G. McCarthy, the daughter of Justin F. McCarthy and Catherine V. McCarthy. We located Brad and Louise in the 1940 census, living in the West Village area of New York City, not far from the jazz clubs where Brad tried to earn a living. His name was misspelled as Branford! The only other guy we've ever heard of with that name is another jazz great, saxophonist Branford Marsalis, of New Orleans.

While in the Big Apple, Brad had a variety of gigs, usually working with other jazz greats. Here he is, playing at a school of all places! The group includes trumpet greats Louis Armstrong, Bobby Hackett and Max Kaminsky, pianist Joe Sullivan, drummer Zutty Singleton, clarinetist Pee Wee Russell and guitarist Eddie Condon:

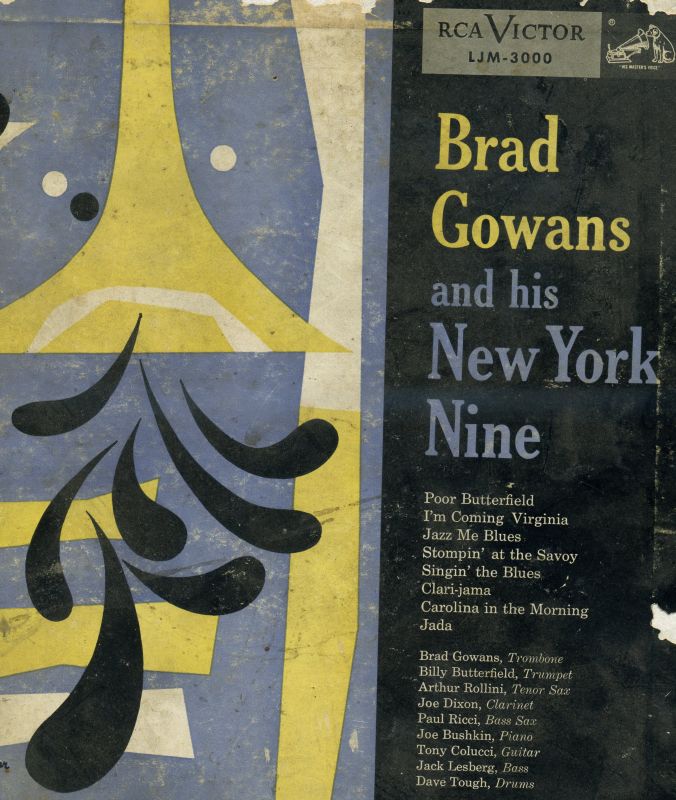

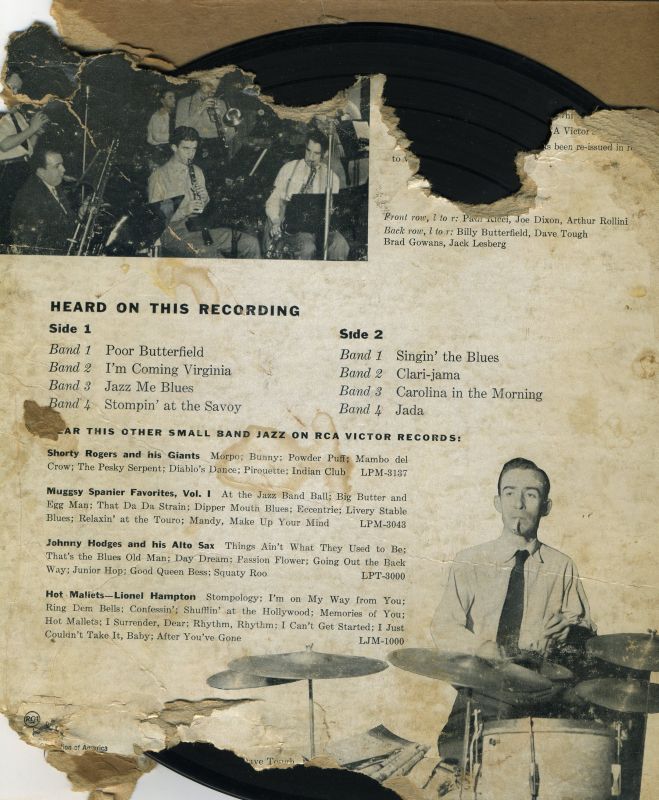

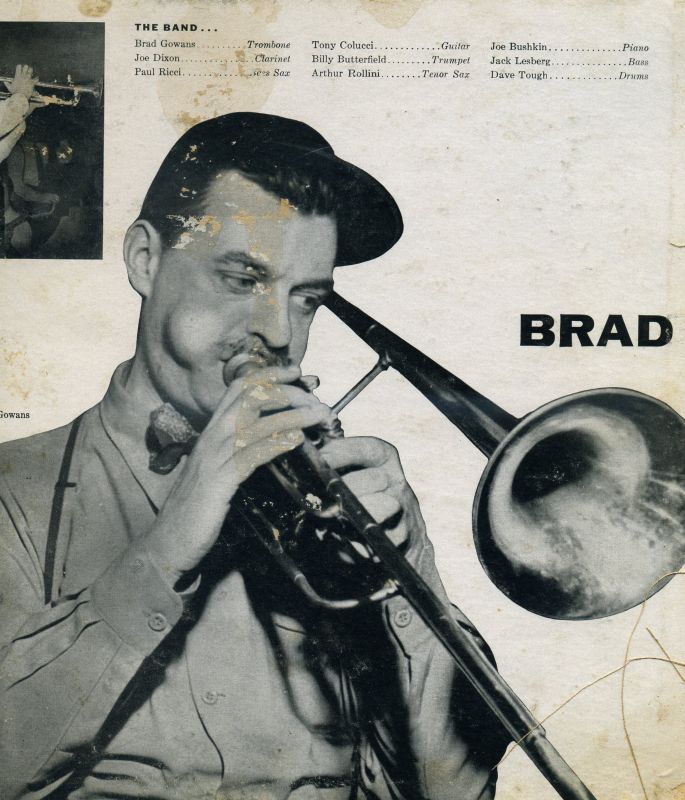

Other than a few 78 rpm singles which Brad recorded early in life, his only recordings as a leader seem to be eight tracks he recorded 10 Apr 1946 which were reissued in 1954 in a 10-inch RCA Victor LP – LJM3000 as Brad Gowans and his New York Nine. I'm not sure that I've ever heard these records, although I own, or have heard, other recordings which Brad made as a sideman.

Here are the front, back and inside covers of that album, which Constance's birth mom gave her when they finally met. Unfortunately it was chewed up by Constance's dog, who also made the vinyl record inside it unplayable. Even though the album contained only a single 10" disc, Victor was lavish in its art work and packaging:

|  |

|  |

| The New York Nine consisted of: | The tunes in the album were: |

|---|---|

|

|

I thought you'd enjoy reading the album's liner notes. We weren't able to determine whether Brad's baseball cap, which the notes mention, was that of one of his home town's two 1946 teams–the Red Sox or the Braves–or of one of the teams alluded to by the album's title–the Yankees or the Giants.

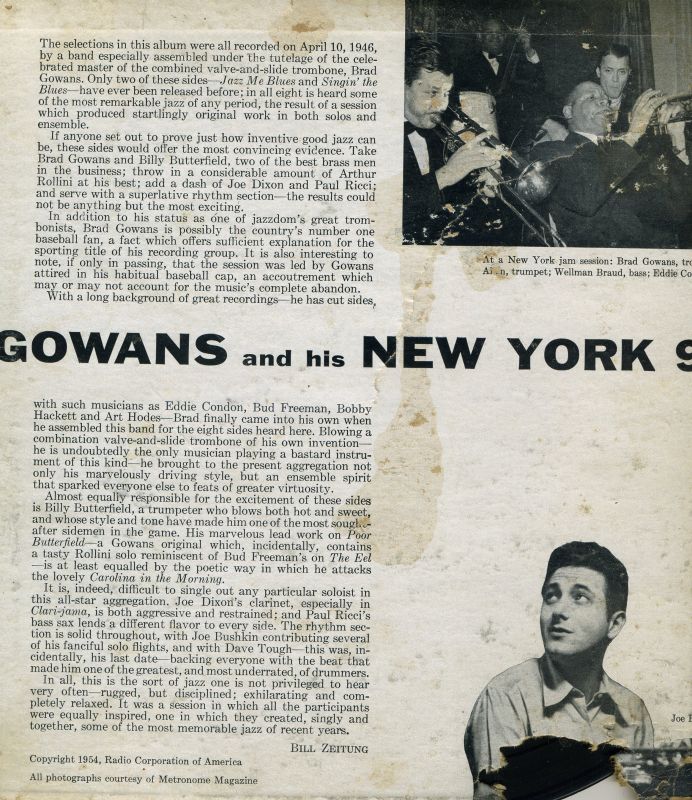

The selections in this album were all recorded on April 10,1946, by a band especially assembled under the tutelage of the celebrated master of the combined valve-and-slide trombone, Brad Gowans. Only two of these sides—Jazz Me Blues and Singin' the Blues—have ever been released before; in all eight is heard some of the most remarkable jazz of any period, the result of a session which produced startlingly original work in both solos and ensemble.

If anyone set out to prove just how inventive good jazz can be, these sides would offer the most convincing evidence. Take Brad Gowans and Billy Butterfield, two of the best brass men in the business; throw in a considerable amount of Arthur Rollini at his best; add a dash of Joe Dixon and Paul Ricci; and serve with a superlative rhythm section—the results could not be anything but the most exciting.

In addition to his status as one of jazzdom's great trombonists, Brad Gowans is possibly the country's number one baseball fan, a fact which offers sufficient explanation for the sporting title of his recording group. It is also interesting to note, if only in passing, that the session was led by Gowans attired in his habitual baseball cap, an accoutrement which may or may not account for the music's complete abandon.

With a long background of great recordings—he has cut sides with such musicians as Eddie Condon, Bud Freeman, Bobby Hackett and Art Hodes—Brad finally came into his own when he assembled this band for the eight sides heard here. Blowing a combination valve-and-slide trombone of his own invention—he is undoubtedly the only musician playing a bastard instrument of this kind—he brought to the present aggregation not only his marvelously driving style, but an ensemble spirit that sparked everyone else to feats of greater virtuosity.

Almost equally responsible for the excitement of these sides is Billy Butterfield, a trumpeter who blows both hot and sweet, and whose style and tone have made him one of the most sought-after sidemen in the game. His marvelous lead work on Poor Butterfield—a Gowans original which, incidentally, contains a tasty Rollini solo reminiscent of Bud Freeman's on The Eel—is at least equalled by the poetic way in which he attacks the lovely Carolina in the Morning.

It is, indeed, difficult to single out any particular soloist in this all-star aggregation. Joe Dixon's clarinet, especially in Clari-jama, is both aggressive and restrained; and Paul Ricci's bass sax lends a different flavor to every side. The rhythm section is solid throughput, with Joe Bushkin contributing several of his fanciful solo flights, and with Dave Tough—this was, incidentally, his last date—backing everyone with the beat that made him one of the greatest, and most underrated, of drummers.

In all, this is the sort of jazz one is not privileged to hear very often—rugged, but disciplined; exhilarating and completely relaxed. It was a session in which all the participants were equally inspired, one in which they created, singly and together, some of the most memorable jazz of recent years.

BILL ZEITUNG

Brad Gowans collapsed on stage while appearing with Eddie Skrivanek's band in Los Angeles in January 1954. The California Death Index not only lists Brad, but also his mother, Ellen F. Gowans, who is said to have been born 14 Apr 1871 in Massachusetts, and died 6 Oct 1961 in Los Angeles county. It is possible his father, Arthur Gowans, died in 1943. This information is based on material contained in queries at RootsWeb.

At one time, the only Brad Gowans obituary we could find was the following, which appeared on page 2 of The Lincoln (NE) Star, 10 Sep 1954:

Brad Gowans Dead

VAN NUYS, Calif. (INS)—Funeral services will be held Friday for trombonist Brad Gowans, 50, one of the music world's leading exponents of Dixieland jazz. Gowans, a native of Massachusetts, died of cancer at his Van Nuys home. He began his career with jazz groups in Boston and later became well known in New York and Hollywood.

But, in June 2017, the obituary below, which appeared on page 1 of the 20 October 1954 issue (Vol. 21, No. 1) of Down Beat magazine, was sent us by trombonist, educator and author Douglas Yeo (be sure to visit his Wikipedia page and his own site!), who is researching Brad for two books he's writing on the trombone:

Brad Gowans, 50, Dies of Cancer in North Hollywood

Hollywood—Brad Gowans, one of music's colorful personalities and a veteran jazz star of the neo-Dixieland era, died of cancer in his home in North Hollywood Sept. 8. Gowans, 50, played clarinet, trumpet, and several other instruments but was best known for his work on an instrument he designed himself—a combination of valve and slide trombone believed to be the only one of its kind.

His last engagement was with Ed Skrivanek's Sextet from Hunger, with which he appeared at the El Cortez in Las Vegas from April, 1953, to April, 1954.

It was there last January that the disease struck him. Following an exploratory operation which revealed that his case was hopeless, musicians and entertainers in Las Vegas staged a big benefit for him, after which he showed a surprising degree of improvement. He was able to return to the band and stayed until the end of the engagement, April 7.

Gowans was born in a small town in Massachusetts, and, like many other jazz men of the era, was largely self-taught.

As a youngster he became something of a disciple and protegé of Eddie Edwards, trombonist with the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and as such was one of the last surviving links with the band that, for better or worse, put the word jazz in the American and other languages. Gowans exchanged letters with Edwards up to shortly before his death.

Among Gowans' last major contribution to jazz was an album, Brad Gowans New York Nine, he did for RCA-Victor about six years ago but which was not released until early this year.

Thank you very much, Douglas!

A few days after sending us Brad's obituary, Douglas sent us two more articles. Both articles were published in 1946. This one was on page 81 of the May issue of Popular Science:

Brad Gowans cites the musical passage above as one that can be played only on one trombone—the Valide, combination valve and slide instrument that he invented and built. Known to millions as an outstanding "hot" musician, Gowans is not widely renowned for the fine machinist he also is.

Since 1922, Gowans has played the slide trombone, clarinet, cornet, saxophone, drums, piano, ballad horn and valve trombone with 27 groups, including The Original Dixieland Jazz Band. He is now playing the Valide in Eddie Condon's band. On the Valide 28 notes can be played in one position without changing the embouchure (position of the mouth against the mouthpiece) as against seven on any other trombone; it can be used as a slide trombone in seven keys by locking down the valves in different combinations, as a valve trombone in four keys by locking the slide in one of its four positions, as a valide by using both methods or one in conjunction with the other. The thumb of the left hand operates the valve lock to add the fifth, sixth and seventh positions to the four-position slide. The middle finger of the left hand holds the slide and tunes the valves when the right hand is being used on the valves. The right hand operates both valves and slide. Where fast changes are involved the thumb and little finger control the slide while the second, third and fourth fingers work the valves.

Other advantages: Valve assembly is moved up close to mouthpiece, relieving player's arms of much weight; short slide avoids danger of smashing slide into some obstacle; many arpeggios impossible of execution on slide trombone can be played; chromatic passages can be played faster; glissando is easier of execution: embouchure is not disturbed when slide is fully extended.

Gowans will not market the instrument, at least not until he finishes a new contract recording for Victor with his own band.

This Young Man (Really) With A Horn also recently perfected a realistic parlor baseball game after 25 years' work. Right now he is installing a 91-cubic-inch, 8-cylinder racing engine in a British Standard Swallow. After he finishes playing with Condon at 4 a.m., that is.

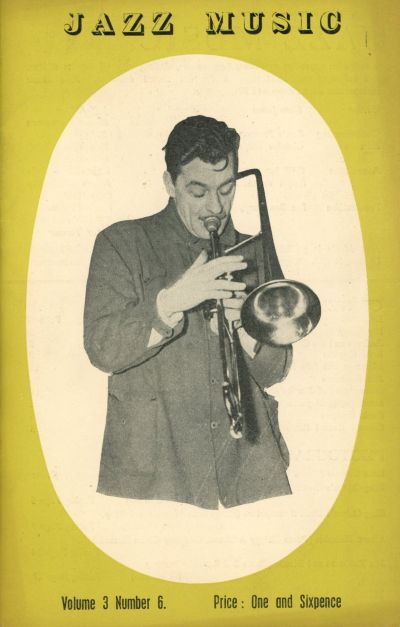

The other appeared in Jazz Music, Volume 3, Number 6, pages 9-13:

BRAD GOWANS

by Ralph Venables"Now, gentlemen," I told the others, "you're going to hear something."

It was Jim Moynahan speaking, his audience a select little gathering of French critics and collectors assembled at the abode of Henri Bernard in Paris, about ten years ago.

I told Henri to put on Heebie Jeebies by the Red Heads, and while he was sharpening a thorn needle I explained to the company what it was 1 wanted them to listen for.

"This date," I said, "was one Nichols invited Gowans along on, but Brad spent the night in a chair in somebody's hotel room and showed up late—with his cornet in a paper bag because the mouthpiece had become jammed. He was too late to make the entire number—they had already rehearsed it without him—but Nichols, perhaps because Jimmy Dorsey kept after him, finally consented to let Gowans take a break in the last chorus. I want you to listen closely to that break, so that you ran recognise it."

Henri started live record, and we listened. In the last chorus the music started to sail, the wood-block clipped out a rhythm, climbed to a break, stopped—and a curiously hoarse instrument, utterly unlike Red's cornet, batted out a short, abrupt break. The music flowed on to a close—again a couple of measures of that curious horn—and ended on a rhythmic pattern with three trumpets—Nichols, Dorsey and Gowans.

The crowd was interested. They made Bernard play the break over several times, demanding to know what sort of instrument it was; it certainly didn't sound like a trumpet.

"It's a cornet," I said, "a little short model like Bix used to play before he came to New York. Brad was going to play a longer break (I hummed it to them) but Nichols made him cut it. Now I want you to look at this next record, note the composer's name, and mark what happened."

The record was Trumbauer's version of Humpty Dumpty, a number by Fud Livingston. Henri put it on, started the phonograph. At the first notes of the theme the men's eyes lighted up. It was the same—the fragment of musical geometry which had been Gowans' tiny contribution to the first record—was here embellished, glorified into a lovely tone-poem! The composer's contribution was unmistakable, but so, too, was his debt.

"This cluck Gowans," I said, half angrily, "is playing in Boston, Mass., and for years I've been trying to persuade him to come to New York and make a few records, but do you suppose I can do anything with him? No, he'd rather spend his afternoons shagging grounders for the North Reading All-Wets."

"But he has made other records?" somebody asked, "Several," I said. "Melancholy Lou and The Camel Walk with Tommy de Rose's New Orleans Jazz Band—the outfit I played clarinet with after Gowans left to go back to Boston. I think he was on Where's My Sweetie Hiding? and Limehouse Blues, on Gennett, with Perley Breed's Orchestra, I know he made Sunny Hawaii and I'm Looking Over a Four-Leaved Clover on Gennett, with a band which included Frank Signorelli, Eddie Edwards, Arnold Starr, Frank Cornwell, the Drewes brothers, Mate Weston, my brother—Fred Moynahan—and me. But Brad's best is Fly to Hawaii on Gennett. On that record he plays clarinet in the first part (he used to play clarinet with the Memphis Five for a while) and then takes a modulation and cornet chorus which everyone I've played it to takes for Bix."

"And what instrument is he playing now?"

"Last I heard," I said, "he was playing valve trombone with Frank Ward's orchestra at the Penthouse of the Hotel Bradford, in Boston. But when I saw him last winter he was on C-melody saxophone. He used to do a one-man band act with Mal Hallett. He would play, in turn, banjo, piano, cornet, drums, trombone, saxophone and clarinet—taking a chorus on each. One night when he was finishing his act and had run through various instruments I hollered out 'Fiddle!' Gowans couldn't play a note on it, and I knew it. The crowd waited expectantly, and the rest of the band were doubled up with laughing. Brad turned a sort of greenish colour and just stood there. It broke up the act, aad we still rib him about it!"

I think the most interesting job Gowans ever played was Tommy Guinan's, in New York. The band was led by Joe Venuti, and had Eddie Lang, Ray Bauduc, I think Jimmy Dorsey, a bass and Gowans. A fellow named Beiderbecke used to drop in evenings and sit in on piano. Quite a band! After this, Gowans played a couple of years for Jimmy Durante when he was with Clayton and Jackson. Jack Roth, of the Memphis Five, was the drummer and leader.

Years before that, I asked Brad to play in my band. He showed up early, with a trombone, and the pockets of his blue serge suit bulging. We were too much occupied with setting-up to stop then for questions, but after we had played the first number I saw I had made no mistake in asking Gowans to join the band—he was terrific! "Do you know a number called Whose Paradise?" I asked him. He asked what key, and when we told him B-flat he said "Okay, wait just a second." We found out then what made bis pockets bulge! He emptied them, dumping a couple of heaps of assorted brass plumbing on the floor, searched among the goosenecks until he had found the section he was looking for, removed a corresponding section from his trombone, replaced it with the other, and turned to us eagerly. "Okay," he said. A typical "Gowans"! He couldn't transpose but, sooner than learn, he had had various lengths of pipe made to fit his trombone, so he could change key and still play in the same positions!

* * * In the ten years which have elapsed since Jim Moynahan recounted those slightly libellous stories of Brad Gowans, of course, the famous valve-trombonist has established himself with George Brunies, and, to a lesser extent, with Miff Mole, Floyd O'Brien and Joe Yukl, as just about the sole surviving members of that select group of white trombone players who are generally regarded as superior to all others—white or coloured. Chief of the Dixieland clan, Eddie Edwards, has proved himself still capable of carving the rest, but in truth today he plays too sporadically to warrant a place in the list. Yet Gowans has always regarded Edwards—and doubtless always will—as the master. Similarly, Jim Moynahan places Larry Shields in a class apart, for Gowans and Moynahan knew the Original Dixielanders thirty years ago—heard them playing and worshipped them from that first encounter. Brad Gowans, like Wild Bill Davison, Art Hodes and several other jazz musicians of outstanding sincerity and talent, today finds himself in the curious position of enjoying considerable public esteem—an esteem acquired only during the past few years, yet he has been playing professionally since the early 'twenties. Arduous indeed is the path of a jazz musician who treads only the righteous road.

Arthur Bradford Gowans was born in Billerica, Mass., on December 3rd, 1903, the first of two sons born to Arthur and Ellen O'Keefe Gowans. His mother, herself a great music enthusiast, encouraged Brad in his eager experiments upon a wide variety of instruments. At the age of ten he submitted to four half-hourly piano lessons—the only musical instruction he ever had—and it was not until 1926 that he decided it was time he could read music. He was playing cornet in Jimmy Durante's Jazz Band then, and set about teaching himself whilst on the job. Progress was rapid, for he had already had a wide experience of playing many instruments—including a bugle in a Boy Scout Troop (upon which he tried desperately to achieve trombone effects with the bugle slide!). He had also played trombone, banjo and C-melody saxophone in various High School bands, and was devoting much of his spare time to the study of the Albert System clarinet. In 1924 he and the Moynahan brothers were the leading lights in the Original Hot Five, and they used to spend all their earnings on trips to New York to see and hear the Dixieland Band. Brad's ambition was to play trombone like Edwards, cornet like la Rocca and clarinet like Shields (in that respect his ideas have undergone not the slightest change) and he regarded them as the absolute ultimate in jazz. Picture his feelings, then, when Tony Sbarbaro sent for Brad to join the band in place of Edwards in the spring of 1925, a somewhat similar situation to that in which Jimmy McPartland found himself when the Wolverines wired for him to replace Bix. But when he reached New York disappointment awaited him. The band had completely broken up, and Sbarbaro had already left town.

Brad was in the depths of despondency, but Edwards (still in New York) felt under a sort of personal obligation to put things right—so he fixed a job for his young friend at Coney Island. Brad sent for Jim Moynahan, and they added Harold McElroy (drums) and Teddy Bartell—but the latter left to join Whiteman. That was a lively job, to say the least, and Brad built up something of a reputation as a trombonist; but it was on clarinet that he went into Tommy de Rose's New Orleans Jazz Band (replacing Sidney Arodin) and on cornet that he then moved to Joe Venuti's band in 1926. Later in '26 he joined the Jimmy Durante hand, and, still on cornet, went from there to Mai Hallett—where he staged his multi-instrument act which fared so well until the heartless Moynahan yelled "Violin"! To Brad, one instrument came as easily as the next, and Bechet's famous One-man Band record would have presented no difficulties to him. "I thought I heard the curious tone, of cornet, clarinet and valve-trombone. . . ."

Gowans stayed with the Mal Hallett orchestra from 1928 to 1930, watching the depression take all America in its grip. 1931 found htm short of work, like so many other hot musicians, and in '32 he accepted a job in the Bert Lown band. Record sessions had been few and far between, consisting of his own Gennett date (Gowans' Rhapsody Makers), two sides with the New Orleans Jazz Band, two with Perley Breed, the famous Red Heads date and a mysterious Edison coupling of Ja Da/Jazz Me Blues which, Brad says, the Mal Hallett band made as a sort of experiment. Was it ever issued? Brad feels sure it was, and recollects Toots Mondello and Andy Russo on the date. By a tantalising coincidence, Jazz Me Blues was waxed by the Bert Lown band (for Harmony) in April, 1929—the very date when Gowans claims to have recorded the number with Mai Hallett—and the cornet work thereon is so startlingly reminiscent of that heard on earlier Gowans' records that the inference seems obvious. Room for investigation here.

There came a lull. Conditions were bad for anyone with a liking for hot music, and Brad had certainly had his fill of commercial orchestras. Then, in 1936, Bobby Hackett came on the scene, organising a small band for the Theatrical Club in Boston. Brad and Bobby joined forces, and in due course they emigrated to New York. In 1937 Jim Moynahan was deploring the fact that Brad was apparently too lazy to seek fame and fortune, but when, shortly after this, Gowans did eventually hit Hew York, he established a reputation with such astonishing rapidity that his musical activities during the next ten years were indeed a prime factor in the whole renaissance of white jazz in New York. Featured on valve trombone with the bands of Bobby Hackett (1937), Wingie Manone (1938), Joe Marsala (1939), Bud Freeman (1940/1/2), Ray McKinley (1942), Brad then led his own all-star group at Nick's in 1943. The following year found him on clarinet in the so-called Original Dixieland Jazz Band touring with the Katherine Dunham show, and, in '46, on valide trombone (combination slide and valve) with Eddie Condon. With that group he appeared in the March of Time film, "Night Club Boom," and with his own hand-picked band he recorded eight sides in April of last year—in Brad's opinion the best work he has done. None of these recordings is yet issued, but a mass of his earlier work with Wingie Manone, Ray McKinley, Art Hodes, Bobby Hackett (notably some superb radio transcriptions with Bobby Hackett's Rhythm Cats), Bud Freeman and Eddie Condon is, of course, available on record. He also cut four sides for Brunswick with Sterling Bose (never released) and four sides with his old friend Eddie Edwards for V-disc, two of which remain unissued, and eight sides for Commodore under Edwards' direction.

From a sort of legendary obscurity, in fact, Bradford Gowans suddenly climbed to high renown, moulding the music wherever he came into contact with it—moulding it to conform with the strict Dixieland pattern which for thirty years he has regarded as the only true jazz. Salutations to a man with the courage of his convictions—the right convictions, to a man of rare musical ability from whose remarkable presence the whole of jazz has benefited during its most important era of development.